There is a joke about the term coup d’état—French for a sudden or illegal change in government. It goes like this: How come there is no word for coup in English? The punch line: Because there is no U.S. Embassy in the United States.

With a wink and a snicker, we know that a headline about a coup in Latin America likely means that the United States was involved. After all, the US has had a long and colorful history of ousting its backyard neighbors when it feels they have gone astray (read: are too socialist). The two most prominent examples being the overthrow of Jacobo Arbenz in Guatemala in 1954 and Salvador Allende in Chile in 1973. Both coups led to dreadful repression in both countries and left a permanent stain on America’s relationship with Latin America and the rest of the world.

But while the US certainly deserves its bad reputation, we need to be on the lookout for those who try to use that history for political ends, because, unfortunately, nothing provides as much political capital (and license for abuse) than claiming that you are the victim of a conspiracy launched by the gringos. From the perspective of a Latin American leader, it’s a godsend.

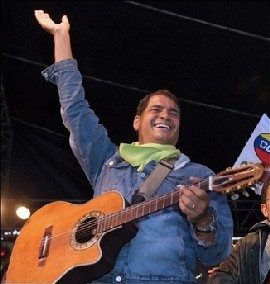

I am, of course, referring to Ecuadorian President Rafael Correa, who was briefly sequestered last week during a nationwide police strike. The disgruntled officers were protesting a new law that ended their bonuses and lengthened the time between possible promotions. Correa—who often displays the diplomatic delicacy of a B-52—went to the police barracks in Quito and tried to bully the striking officers. While puffing up his chest and pulling at his shirt, he said, "If you want to kill the president, here he is. Kill him, if you want to. Kill him if you are brave enough."

Apparently some were. As he was leaving the barracks he was tear gassed by some of them. Yet other officers helped him get to a nearby police hospital. But it wasn’t over. Many of the police, still incensed, surrounded the hospital trapping Correa inside for eleven hours. In the end, cooler heads prevailed and the president was freed.

But more disturbing than the actual incident—which appears to be a spontaneous eruption by low level officers that was condemned by senior officers—is Correa’s immediate attempts to depict it as something much bigger than it was, calling it a coup, insisting that there had been a plot to kill him, pointing his finger at his political opponents, and insisting that he had been rescued by el pueblo.

Curiously, this is exactly the same narrative that Correa’s ally, Hugo Chávez, has been spinning in Venezuela ever since his 48-hour arrest in 2002. While I myself had initially believed that Chávez had been the victim of a “classic coup,” five years of research proved me wrong. Chávez himself had sparked the crisis. Indeed, the Venezuelan authorities had a legitimate reason for taking him into custody—his supporters had been responsible for opening fire on an opposition protest as it converged on the president’s palace and there was credible evidence that Chávez himself had approved the use of violence. It was only in the aftermath of the crimes committed by the Chávez government that the Venezuela military, similar to the Honduran military in the ousting of Manuel Zelaya, broke the law by attempting to deport the president illegally.

When Chávez was restored to power, he used the uprising to maximum effect: he shut down TV stations, jailed union leaders, packed the Supreme Court, and persecuted his political opponents all under the guise of protecting himself from “coupsters” controlled by the United States.

Speaking of the assault on Correa, Chávez said, “It would be very naive to think that this is motivated only by salaries….We are facing a new attack from the fascist beasts—it’s a coup attempt.”

Unfortunately, “pulling a Chávez,” appears to be exactly what Correa is doing, which is, as much as I hate to admit it, smart politics.

If Correa can convince the masses that he was the victim of a coup, everything changes. A policeman’s strike is not a strike at all, it’s an insidious plot; his political opponents are no longer just dissenters, but puppet’s of the CIA; and the opposition media can be neatly recast as part of Washington’s campaign of psychological warfare. In this way, Correa becomes David versus Goliath. It’s smart politics…but it’s terrible for democracy. Whether real or imagined, a coup attempt is the perfect rationale for breaking your country’s laws in the name of self-preservation.

It is too early to see how far Correa will try to take this, but he will likely milk it for all it is worth. His recent threat to dissolve congress should it block his reforms is not a good omen. Let us hope that he shows more respect for democracy than Hugo Chávez.